The Grave of Memories: Purpose and Composition of Memory in Grave of the Fireflies

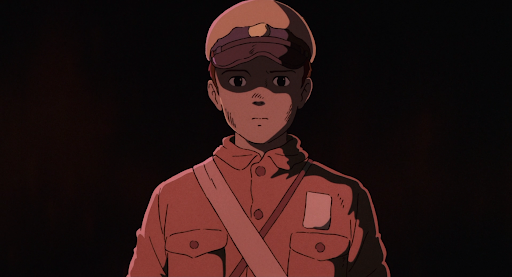

By the time Japan entered the 1980s, an aroma of excess wealth emanated from its strong economy. The images of its torn down cities, burned down homes and poisoned rivers were plastered over by futuristic skyscrapers, humming factories and bullet trains. Those who live in that era might have showered in luxury items, forgetting what life used to be like decades earlier. But it was this same stage that Studio Ghibli’s Grave of the Fireflies was released in 1988. The film reminded both Japan and the world of the atrocities and misery during the last few months of the Second World War. Many tend to look at the film as an experience far divorced from the present; however, viewing the film in the context of this era is particularly insightful. The film’s form is carried by two versions of the male protagonist, Seita. One version depicts his past. The other depicts his present, a state in which he has already died. Throughout the film the two never directly interact, yet they are often placed in the same frame. This indicates that while we see the past and the present as separate events, it is still crucial to see how they connect with each other to form the basis for what we believe to be a realistic account of events. More importantly, the audience is placed in a position to consider how reality is constructed from multiple pieces of memories – one being Seita and his sister, Setsuko.

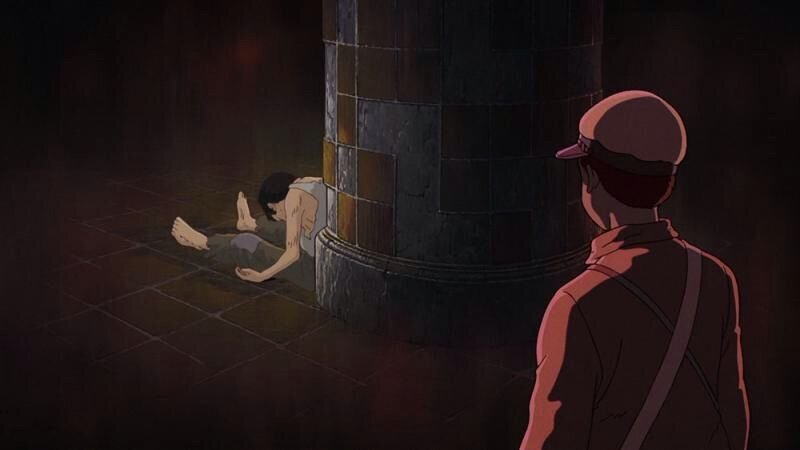

The prevalence of memory is highlighted in an earlier scene in the movie. Soon after collecting his mother’s ashes, Seita heads off to his aunt’s house. On the train, he tightly holds onto the box that contains his mother’s remains while drifting off in his own thoughts. The train’s interior is paved with wood and filled with civilians and soldiers in brown clothes. In a sense, there are warmth and coziness that ooze off from this brown interior. But then the camera slowly pans forward to the audience. In doing so, the realm of the past Seita merges with the present Seita whose realm is colored in red. Present Seita’s realm creates a tension between the present and past. While his side of the train is empty, Seita’s face is fixed on his past self on the brown side of the train. When the train arrives, we are still in the present Seita’s realm. Seita gets off with Setsuko and walks to the top of the hill where the past and the present meet once again; except this time, a larger physical distance has been created. Down the hill, past Seita makes his way to his aunt’s house. Around him were rice paddies that give off a dark blue tone. The camera cuts to the present Seita’s face as he stares intensely at his past self, quiet and unable to do anything.

The tension between the present and past memories can be seen since the 1960s, the decade in which the book this film was based on was published. In an NHK TV discussion broadcast towards the end of the decade, some college students refuse to look at wartime memories nostalgically. They believed in memories’ importance, but they raised the question as to why they need to inherit something that was not theirs. They argued that if the memories cannot create anything, they are just complaints.[1] While this difference is shown through spatial separation in the film, the chasm between the past and the present of 1960s Japan is in the mind of its citizens. The younger generation that emerged after the war showed an eagerness to move away from the past or even to bury it. Their eagerness can be partially explained. Until the 1960s, the Occupation censorship created a scarcity of media and literature sources related to the memories of war. The US needed Japan to adopt a more active role in international politics as a response to the rise of the Soviet Union and Communist China. Because of this, they revised education textbooks to emphasize democracy and a new Japan.[2] The past was slowly buried as the new world, the beginning of the Cold War, was coming to light. This might be the same as Seita as he tries to bury the memory of his mother (which he fails to do so in the end) while heading off to his new life. In his head, he thinks that the life he will forge can be disconnected from his past trauma. This might be the narrative that the college students in the broadcast believed. If one can go on living in the present, unchained from the past, why should past memories be important? But with criticism over past memories, the present Seita points to his past self. At this point in the film, the viewers think that Seita’s life is heading on a smooth course. However, the serious expression that emerged on the present Seita’s face contradicts the easy-going life of past Seita, prompting the audience to wonder whether something might go wrong.

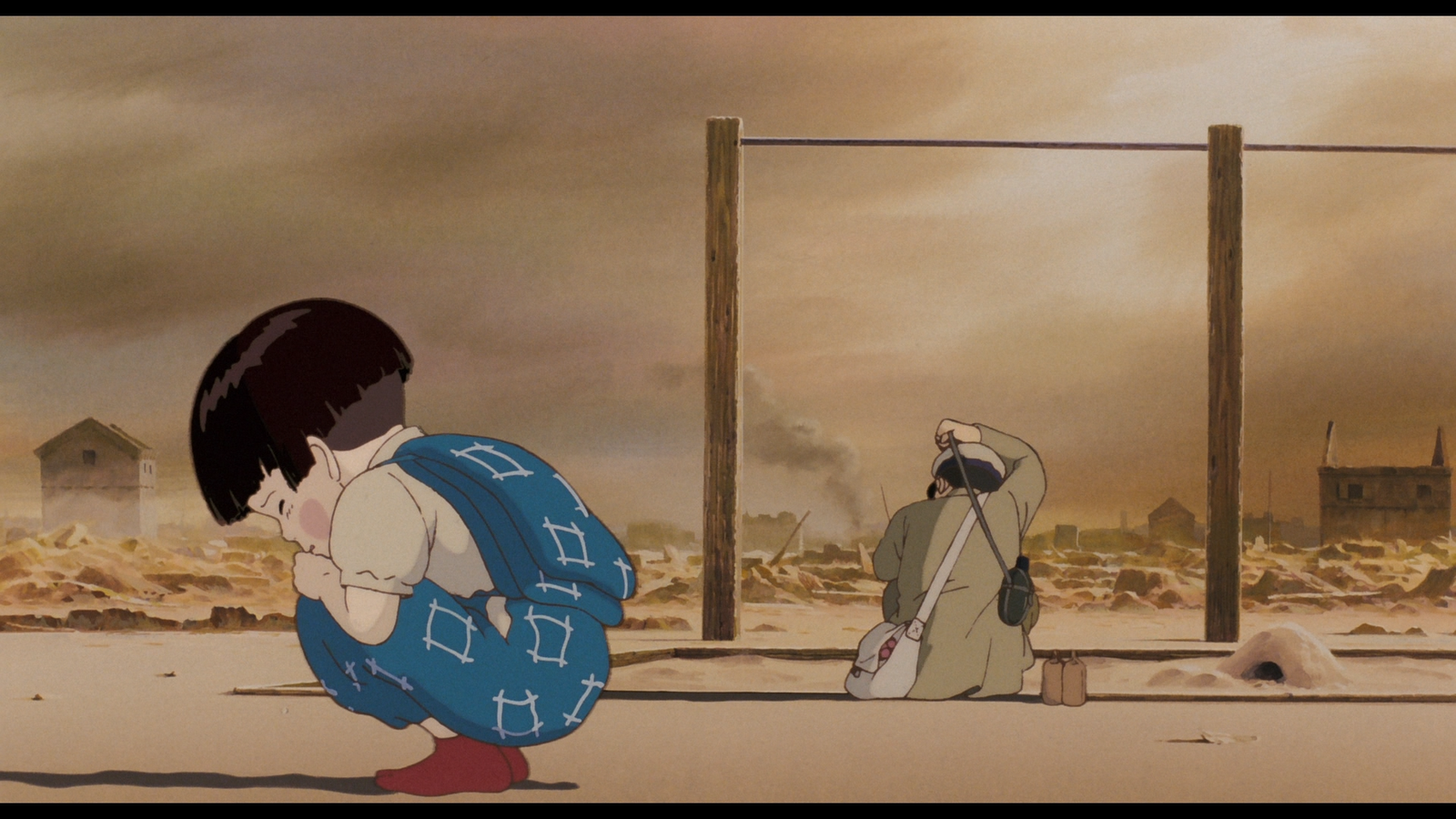

In fact, that revelation holds true as the audience is taken on a poignantly painful ride towards the decay of Seita and Setsuko. They eventually arrive at the hill in which a brother has to cremate his own sister. After the cremation, present Seita appears and he reunites with Setsuko. For the first time in the film, he says something. “It’s late,” he tells Setsuko, “time for bed, okay?” Setsuko agrees and sleeps on his lap. Seita’s face turns serious again and looks outward. At this point, the audience does not know what he is looking at. The camera cuts to a close up of Setsuko who is slowly breathing and sleeping peacefully on her brother’s lap. In the final scene of the film, the camera cuts to a wide angle shot where the foreground is drenched in blood red, and the background, a 1980s Kobe dotted with skyscrapers rises in neon blue. The camera slowly pans upwards; Kobe rises while Seita and Setsuko sink. More and more, the network of buildings and roads become apparent to the viewers while the siblings, now tiny once scaled against the city, slowly dissipates behind the pine tree branches of the foreground. As the scene fades to black, the audience comes to a chilling realization that they are the subject of Seita’s deadly state – the same one he casts on his past self. The role changes as recollections of the past comes to an end: the present Seita, the one we see in red, becomes the past. The 1980s Kobe, the embodiment of the viewers, becomes the present. The color switches as well. The red becomes the past and the blue becomes the present. It is as if the film now highlights us, or more accurately 1980s Japan, as a naïve past Seita who headed towards destruction. The Seita who is drenched in red represents a memory, separate from space and time, and invisible to us all. The color switching therefore plays a large role in showing that this realm of memory is beyond our present consciousness.

In the 1980s, the decade in which this film was released, the perspective on memory became more self-reflective. In other words, Japan accepted its wartime memories, but it was more interested in dealing with its own image that emerge from these memories. Domestically, a wave of patriotism emerged. This wave has begun since the 1970s when the government who wanted to restore some of its prewar education policies started requiring schools to sing the national anthem and raise the national flag. While there were oppositions coming from the teachers, it was clear that by the late 1970s, the government was trying to alter memories of the war.[3]

This education reform placed Japan in a paradoxical position. With a strong economy that gained momentum in the 60s, Japan needed to look to foreign markets to sustain its own economy. On the other hand, with these controversies raging in the background, Japan found it very difficult to normalize relationships with China and Korea, its two closest neighbors. The obstacle intensified when the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), the party that is still dominant in modern Japanese politics, won the majority of both houses in 1980; with their ascent, patriotic education started to gain traction.[4] The LDP set to work in trying to portray the Second World War in a more positive light with the aim of evoking pride among younger Japanese.[5] It was then the children, ranging from Setsuko’s to Seita’s age, who were the subjects of this education reform. In 1982, the LDP-dominated government exerted pressure on textbook publishers to change words that indicated Japan’s wrongdoings. For example, the word “aggression” (shinryaku) was changed into “advance” (shinshutsu) and the Korean independence movements were painted as ‘Korean riots’.[6] Additionally, textbooks that came after 1982 separated the Japanese ‘nation’ from the Japanese ‘state’ where the ‘nation’ were victims to the militarized ‘state’.[7] When altered in this way, the nation can celebrate its identity more positively, allowing for what is believed to be a healthier nationalism.

But Seita’s gaze does not seem to indicate that we need to identify a physical manifestation of a ‘victim’. He looks out to a vast urban landscape where we cannot even see its residents. For the point of the film is not to create a dichotomy between the oppressor and the oppressed. The Japanese government and American soldiers are rarely seen throughout the film. Rather it is there to show the chasm between the present and the past as emphasized by the opposite colors that depict these two timelines. In the film, red Seita and Setsuko barely talked. They also cannot be seen by their past selves. If we take them as the embodiment of memory, then we cannot see memory or hear it outside of a medium – in this case, it is the film itself. But memories can come through different forms of mediums. It can be communicated through textbooks, television, films and oral stories. These diverse mediums indicate that events that occured in the past are constructed from pieces of memories. If a narrative is formed from just one source, the whole story is not complete. Other important pieces of memories might remain with the millions of Setsukos sleeping under the shade of the pine trees, invisible to all of us.

Seita’s appearances as both his past and present selves point to both the importance and the composition of memory. The film shows that what the students in the NHK broadcast pointed out to might be the wrong purpose of memory. It might not be there to create something new. Instead, it is there to make sure that we avoid doing the same things as the past, which in itself creates value as well. After seeing how Seita’s naïve past self falls into an abyss of misery, the audience might look back to mistakes they could have avoided in their own lives. The depiction of Seita and Setsuko as tiny children atop a hill overlooking a futuristic Kobe turns the siblings into a piece of memory. The film argues that memory does not reside in just one person. If this film were to focus on the perspective of Setsuko, we might get a totally different reality. But since there is Seita as well, we get to savor a fuller picture. Taking a step back, the memories of the war extend beyond Seita and Setsuko. These memories reside in a generation that is slowly fading away, as seen through the college students’ skepticism. If memory is tucked away or altered by only one party, past events will be hidden from the present, creating a division that can never be bridged. And in this scenario, just like how Seita hopelessly looks at himself, Japanese wartime memories cannot deter present Japan from falling into the same disaster. If reality is not pieced together collectively across many different generations and across various mediums, some important crumbs of memories that make up reality will slowly fade away on a hill, behind the pine trees, somewhere in an unknown corner of the world.

Notes

[1] Igarashi, “Re-Presenting Trauma in Late-1960s Japan.”, 166

[2] Lawson and Tannaka, “War Memories and Japan’s ‘Normalization’ as an International Actor: A Critical Analysis.”, 414

[3] Takashi, “Historiography of the Asia-Pacific War in Japan.”

[4] Lawson and Tannaka, 415

[5] Ibid., 415

[6] Ibid., 415

[7] Ibid., 416

Bibliography

Igarashi, Yoshikuni. “Re-Presenting Trauma in Late-1960s Japan.” In Bodies of Memory, 164–98. Princeton University Press, 2000. https://www-jstor-org.proxy.library.cornell.edu/stable/pdf/j.ctt7s2kh.10.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Af1c2c328cf57dd87596a89952005d9ef.

Isao Takahata (dir.). Grave of the Fireflies (Hotaru No Haka). Widescreen ed. Vol. pt.1-2. New York : KALTURA, n.d.

Lawson, Stephanie, and Seiko Tannaka. “War Memories and Japan’s ‘Normalization’ as an International Actor: A Critical Analysis.” European Journal of International Relations 17, no. 3 (n.d.): 405 – 428. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066110365972.

Takashi, Yoshida. “Historiography of the Asia-Pacific War in Japan.” SciencesPo, June 3, 2008. https://www.sciencespo.fr/mass-violence-war-massacre-resistance/fr/document/historiography-asia-pacific-war-japan.html.